Ozone Depletion

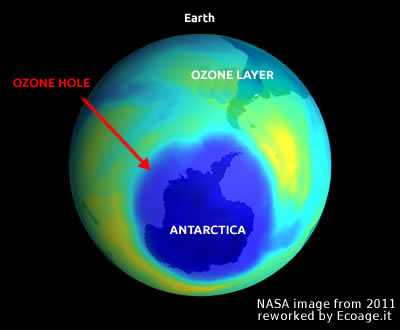

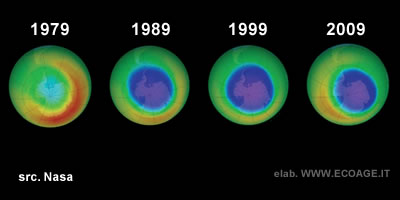

The ozone hole refers to the thinning of the ozone layer (O3) in the Earth's atmosphere, which protects us from the sun's harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This thinning is a serious threat to both our health and the environment. It is caused by pollutants released into the atmosphere through industrial and consumer activities. In particular, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are the main culprits behind ozone depletion. Currently, the ozone hole is mainly located over the South Pole, and it is expanding by 5% every decade. This issue is one of the most significant environmental challenges we face, as it threatens life on Earth.

Why does the ozone hole form over the poles? The depletion of the ozone layer primarily occurs in polar regions because these areas receive less sunlight, which is essential for the photochemical reactions that create ozone. Furthermore, cold temperatures in these regions accelerate the breakdown of ozone.

The term "ozone hole" is easy to remember and widely recognized, but it can sometimes lead to misunderstandings as it doesn’t fully explain the phenomenon. A more precise term would be "ozone layer depletion" or "ozonosphere depletion," as these better capture the complexity of the issue and avoid the oversimplification of a serious environmental problem.

What is ozone?

Ozone, or trioxygen, is a molecule made up of three oxygen atoms (O3). It exists as a bluish gas in the Earth's atmosphere and forms naturally through the activity of cyanobacteria, which produce oxygen (O2) as part of their life cycle. Over time, a significant portion of the oxygen in our atmosphere has been generated through this process. In the atmosphere, molecular oxygen (O2) combines with single oxygen atoms (O) to form ozone (O3).

Ozone forms in the sunlit regions of the stratosphere near the tropics and is then transported to the poles and higher latitudes due to global air circulation. Over time, ozone molecules have accumulated in the upper atmosphere, forming a protective layer that absorbs harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. This ozone layer, called the ozonosphere, is located in the stratosphere at an altitude of about 20-30 kilometers above the Earth's surface. The thickness of the ozone layer varies depending on the geographic location—it's thinner near the equator and thicker at the poles. Thanks to the ongoing photochemical reactions between oxygen molecules and sunlight, the ozone in the atmosphere is constantly replenished, maintaining the balance of the ozone layer.

For more details, refer to our page on how atmospheric ozone is formed, where the chemical reactions behind this process are explained in depth.

Why is the ozone layer important?

The thin ozone layer made it possible for life to transition from the oceans to land, enabling the evolution of terrestrial species. Without this atmospheric shield, life as we know it would likely have remained confined to the oceans. The importance of the ozone layer becomes clear when we realize that without it, humanity would not exist. The ozone layer absorbs 100% of UVC rays and around 90-95% of UVB rays, which are the most dangerous forms of ultraviolet radiation for living organisms due to their high energy. It allows less harmful UVA rays to pass through, which are essential for maintaining the balance and proper functioning of ecosystems.

What causes the ozone hole?

Throughout Earth's history, the thickness of the ozone layer has fluctuated naturally. However, since the mid-20th century, human activities have led to a rapid thinning of the ozone layer. The introduction of pollutants, particularly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) used in aerosol sprays and refrigeration systems, has significantly impacted the ozone layer. CFCs consist of carbon (C), fluorine (F), and three chlorine atoms (Cl3). In the upper atmosphere, solar UV radiation breaks down CFC molecules, releasing chlorine atoms. These chlorine atoms then react with ozone (O3), forming molecular oxygen (O2) and a free oxygen atom (O). This process destroys ozone (O3), which is what causes the ozone hole.

One chlorine atom released into the stratosphere can destroy up to 100,000 ozone molecules before returning to the troposphere (ecoage.it). During the 1970s and 1980s, international agreements led to the banning of CFCs, and the scientific community continues to monitor the issue closely.

Natural fluctuations in the ozone layer have occurred gradually over time, allowing life to adapt. In contrast, human-induced changes have been much more abrupt. This rapid pace poses a serious threat to the balance of our planet's ecosystems and biosphere. The most severe ozone depletion occurs over Antarctica, which is what we refer to as the ozone hole.

The consequences of ozone depletion

The effects on living organisms

The ozone layer acts as a protective shield for living organisms, blocking the most intense UV radiation from the sun. If this layer thins, higher-energy UV rays would reach the Earth's surface, putting human health and all life on the planet at risk.

- High-intensity ultraviolet radiation can cause irreversible damage to cells, leading to skin cancer, including melanoma.

- These rays can also interfere with genetic material, altering the DNA and RNA molecules in living organisms.

- Another dangerous consequence of UV-B exposure is irreversible damage to the retina, which can lead to blindness.

Living organisms have evolved over hundreds of millions of years, while ozone depletion has occurred over just a few decades or centuries. This external shock is happening too quickly for life to evolve and adapt.

Note: In small doses, ultraviolet radiation is not harmful to human health. In fact, it stimulates the production of vitamin D. However, excessive exposure can cause significant damage.

The effects on the environment

Harmful solar radiation can disrupt photosynthesis and stunt the growth of plants and phytoplankton in the oceans. Additionally, microscopic organisms are particularly vulnerable to excessive UV exposure. Since plants and phytoplankton form the base of the food chain, any disruption could have serious consequences for the entire ecosystem.

Effects on agriculture and fishing: A reduction in plant growth would negatively impact agricultural yields, while the loss of phytoplankton would harm marine life and fisheries. With the global population continuing to rise, food production may struggle to keep up with demand. This concern was first highlighted by Malthus in the 19th century.

When solar radiation becomes too intense, the environment can become inhospitable for many species, including humans. Only a few life forms could survive in such extreme conditions, enduring constant exposure to high-energy rays. For example, insects with exoskeletons might have a better chance of surviving, but even they would have to live in a barren, desolate world with little to no vegetation.

What is being done to address the issue?

Ozone depletion remains one of the most significant environmental challenges we face today. Various measures have been implemented to tackle the issue, including international agreements like the Montreal Protocol of 1987, which came into effect in 1989. Signed by 196 countries, the protocol aims to reduce the production of ozone-depleting substances and replace CFCs with less harmful alternatives, such as eco-friendly propellants.

A NASA study in 2018 confirmed the link between CFCs in the atmosphere and ozone destruction. The results showed a steady decrease in CFCs over Antarctica (0.8% per year), indicating that the Montreal Protocol is helping to reduce ozone depletion. However, the long-term effects of these efforts remain uncertain. The size of the ozone hole continues to fluctuate unpredictably. In recent years, the rate of ozone depletion has slowed over the South Pole but increased in surrounding areas in a complex, chaotic process that requires ongoing scientific monitoring.

Why does ozone deplete faster at the poles?

Although the polar regions have a thicker ozone layer, depletion occurs more rapidly in these areas due to lower sunlight exposure, which reduces the number of photochemical reactions between ozone molecules and sunlight. Additionally, colder temperatures contribute to ozone breakdown. In these regions, ozone production is too slow to offset the destruction caused by pollutants like CFCs and other substances released by human activities.